git fire

Intro

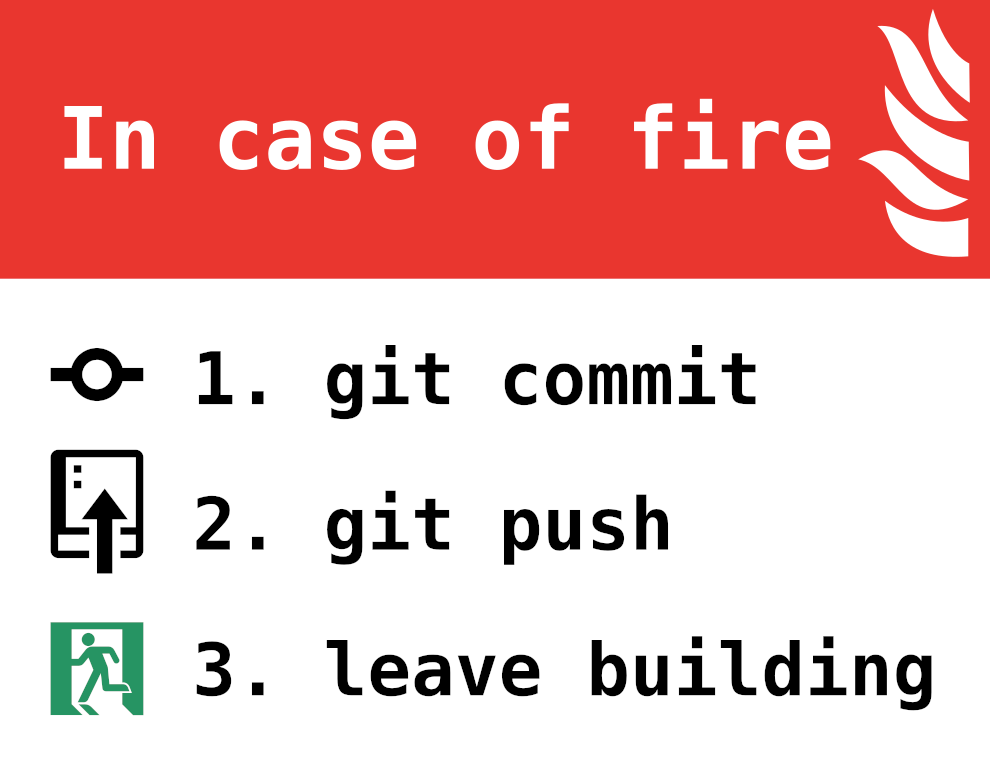

When wandering through the floors of university buildings I came across stickers on office doors like the following several times:

While in the first moment such stickers are funny, on a second thought they also induce a slightly bitter taste of "well, actually ...".

I want to breakdown my critique for each of the three points individually and propose a solution.

The Problem with "git commit"

The plain command git commit serves to commit the content of your staging area to the repo. This means if the user did not by chance execute git add immediately before it will likely result an incomplete or even empty commit (whereby the latter would be refused by default). Thankfully git commit offers the --all option (short version: -a) which automatically adds all modified files to the staging area which have already been tracked before. While this leaves newly created (and yet untracked) files in peril of data loss, it seems to be the saver option for a general emergency recommendation (which might be automated, see below). The alternative would be to call git add . which would stage every modified file in the directory – including untracked ones – and thus bear the risk of accidentally sharing unwanted information such as credentials. Of course, proficient and responsible git users would have explicitly added suitable patterns to their .gitignore file but it cannot be assumed that the complete target audience of a git commit; git push-guide has enough background knowledge for this safety measure.

The second problem with the plain git commit command (which also affects git commit -a) is the lack of a specified commit message. This would therefor fire up (pun intended) the default editor and prompt for a commit message -- which is probably not the desirable behavior of a emergency command. Hence the recommended version for the first command is:

git commit -a -m "emergency commit"

The Problem with "git push"

The plain command git push also has its issues. From my experience it could fail for three reasons.

- There is no remote configured for the whole repo.

- There is no remote tracking branch configured for the current branch.

- The current branch has remote changes.

I will leave reason 1 alone because there is no general solution to it. If fire breaks out and you have not yet configured a remote (e.g. at https://codeberg.org) then git cannot help you much and you might be better of to save your work to a USB drive. Chances are high, that your project was in a very early stage anyway and thus the amount of losable data (including version history) is probably low.

Reasons 2 and 3, however, can occur also in mature projects. Both can be addressed with the same measure:

-

a) creating (and checking out) a new branch before running git commit:

git checkout -b emergency-backup- b) Explicitly specifying the remote tracking branch when pushing:git push -u origin emergency-backup

This assumes that the branch name "emergency-backup" does neither exist in your local repo nor in the remote. If this mild assumption is valid, it prevents conflicts (reason 3) as nobody could have pushed to that branch. It also prevents the problem of a possibly unspecified remote tracking branch by simply explicitly defining one (which, however, is independent of your actual working branch).

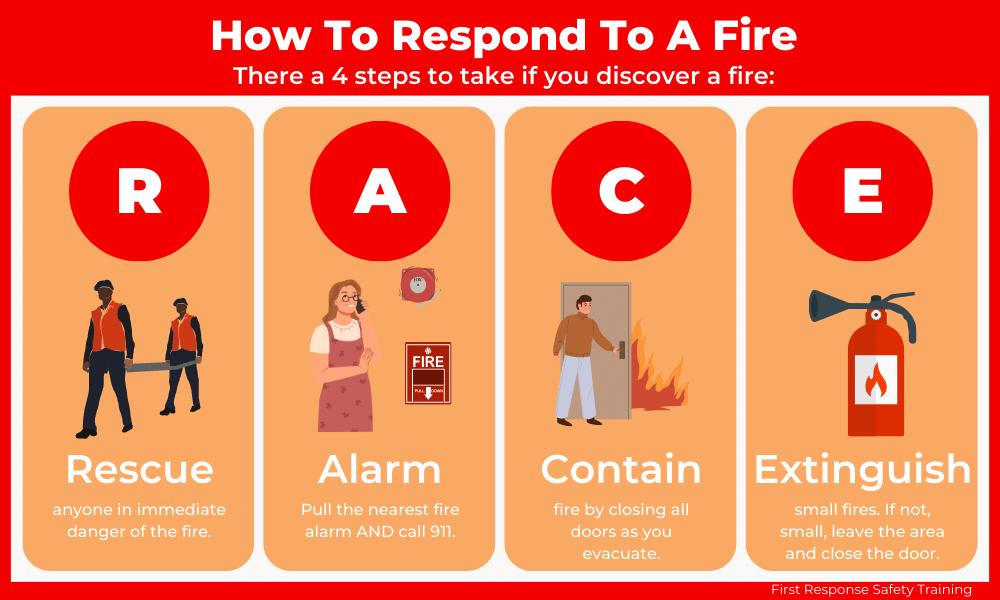

The problem with "leave building"

While the humor of the above meme is based on the fact that there are three short instruction, the last one implies a pretty egoistic character. It should not be forgotten that there are established rules on how to behave in fire-related emergency situations. Simply leaving the building is most likely not the whole story. The exact recommendable actions usually depend on the local circumstances (and should be propagated e.g. via mandatory trainings and signage) but something like the R-A-C-E steps might be a good orientation:

The bottom line is: You are not alone on the world! If you have time to save your project work you should also have time to prevent damage for other humans and material assets.

Wrap up

The recommended sequence of commands is:

git checkout -b emergency-backup

git commit -a -m "emergency commit"

git push -u origin emergency-backup

Obviously, this is less rememberable than the original git commit-git push-sequence, but thankfully it could be defined as an alias with the single command:

git config --global alias.fire '!git checkout -b emergency-backup && git commit -a -m "emergency commit" && git push -u origin emergency-backup'

Once this alias is defined, in case of emergency it suffices to run

git fire

and then concentrate on what is actually important: saving humans and if possible mitigating material damage.